AI insights

-

What is identified as the main business problem in the primary article?

The article states that the core issue is drift, not speed. It notes that leaders are moving away from Figma-first workflows toward prototypes in code and system-level thinking to reveal the truth earlier and reduce intent leakage and model churn.

Topic focus: Core Claim -

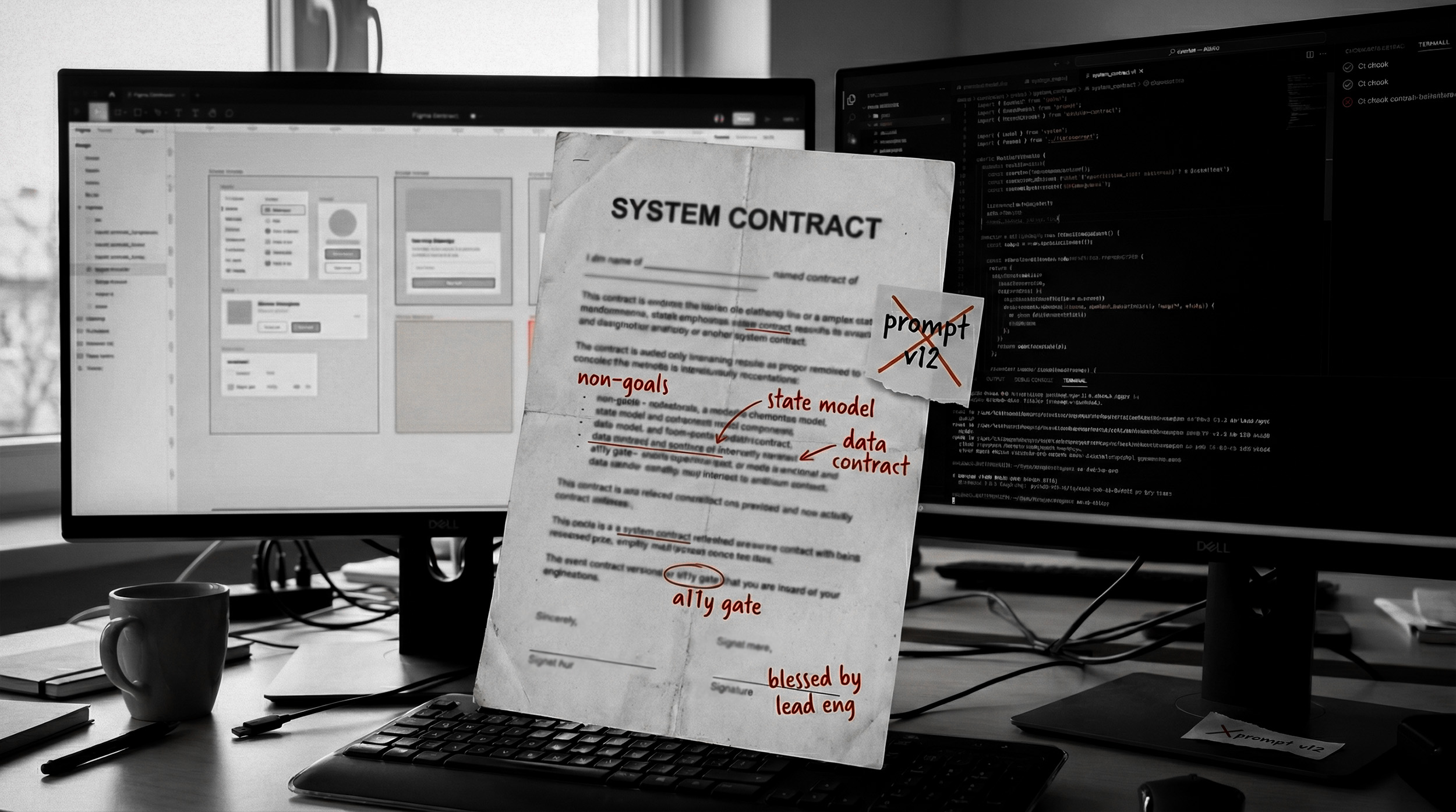

What model is proposed to address this problem?

A System Contract model is proposed to eliminate intent leakage and model churn. This framing is highlighted in the meta description as the approach designers are adopting.

-

What deliverables do leaders prefer over traditional Figma outputs?

Leaders want prototypes in code that run, not static Figma deliverables. They seek to see the truth earlier and avoid translation issues between design and implementation.

Topic focus: Data Point -

What leadership ritual is suggested to prevent drift, and where does it come from?

A 15–20 minute structured clarity ritual is proposed as speed insurance to prevent months of unwinding a confident mistake. This ritual can be used when authoring decisions or approving them.

Topic focus: Pitfall -

According to The Spiral Climbs, what shift is occurring in design tooling and practice?

Design is moving toward systems, tokens, and code; patterns are cheap and the distance from idea to code is shortened. Live artifacts inside tools beat static decks, enabling faster feedback and continuous iteration.

Topic focus: Data Point -

How many rules are presented in 15 Rules of Design Leadership for 2026, and what is a key motto?

There are fifteen rules proposed for 2026. A recurring motto is making ideas happen, with an emphasis that humans are the system too.

Topic focus: Definition -

What related resources are recommended for further reading?

For broader context, consider reading The Spiral Climbs and Leadership in the Age of Infinite Fluency, along with the 15 Rules of Design Leadership for 2026 as additional guidance.

Topic focus: Next Step

- Leaders increasingly want prototypes in code rather than Figma, pushing for earlier truth about feasibility and risk, not prettiness.

- This drift happens when intent leaks from design files into tickets and merged code, creating costly maintenance later.

- The fix is a System Contract with a machine-readable Constraint Stack that codifies invariants, data contracts, and acceptance checks.

- Someone must own the translation into machine checks, and reviews must be diff-friendly and human-reviewable to prevent fog and rushed approvals.

- Figma is still valuable for aesthetics, but the repo and tokens are the source of truth, with automation verifying behavior and preventing divergence over time.

I was at an event the other day, the kind where people wear the right shoes and talk about “strategy” like it is a physical object.

In the middle of a conversation with a few leaders, somebody said it out loud.

“We don’t use Figma anymore.”

Another leader went further. They said they hesitate to work with designers who treat Figma as the main deliverable. They want prototypes in code. They want something that runs.

That statement can sound like a threat if your entire career has been built around being the best person in the Figma file.

I do not think it is anti-design. I think it is anti-translation. It is leaders saying, “Show me the truth earlier.”

If you are hearing this more often, you are not imagining it. I hear the same anxiety in mentoring sessions every week. People are not asking, “How do I use AI?” They are asking, “How do I stay relevant when execution is cheap?”

This is where DesignOps AI becomes more than a trendy phrase. It is a shift in what we treat as truth and what we treat as overhead.

The business problem is drift, not speed

Speed is the headline. Drift is the invoice.

In most organizations, intent leaks between a design file and a merged pull request.

It leaks through tickets.

It leaks through interpretation.

It leaks through “I thought you meant” conversations that show up when the deadline is close, and everyone is tired.

Call that intent leakage. It is the difference between what was meant and what shipped.

The worse, the bill arrives later.

Six months later, a feature needs to change.

The original context is gone.

The rationale is gone.

The edge cases are gone.

The system rules that were “obvious” at the moment are nowhere to be found. The team treats the feature like legacy code. They touch it carefully, they break it anyway, and they pay for it twice.

Call that maintenance leakage. It is the cost of lost context.

AI turns both problems up.

It makes it easier to produce a prototype. It also makes it easier to produce the wrong prototype quickly. When output volume goes up, divergence risk goes up too.

Then comes the fear that leaders rarely say directly.

Model churn.

Prompts rot.

Tools change.

Context windows shift.

Vendors come and go.

If your workflow depends on a fragile set of prompts and remembered instructions, you are building on sand.

This is why the System Contract matters. Not because it is elegant. Because it reduces risk and gives you leverage.

Yes, it is insurance against lock-in. Your truth lives outside the chat, so you can swap ChatGPT for Gemini, move to a local model, or change agent tooling without losing direction.

But it is also cost control.

When the System Contract is stable, you do not need the biggest model for every job. You can use a heavy model for messy reasoning and synthesis, then hand off the boring verification work to lighter, cheaper models.

What makes that safe is the technical layer inside the System Contract. The Constraint Stack. The machine-readable files that tools can check.

Linting. State-transition checks. Contract checks. Regression summaries.

That is a leader’s argument.

Why code prototypes are winning the argument

Figma is still excellent at what it was born to do. It makes a shared visual language fast. It helps teams talk.

The trouble starts after the file is blessed.

A high-fidelity Figma prototype can look done while hiding the things that break products in the real world.

Latency. Real data. Permissions. Error states. Accessibility behavior. Performance constraints. Browser quirks. The small ugly truths.

A code prototype surfaces those truths earlier. That is the point.

When leaders say “ship it in code,” they are usually chasing three outcomes.

Less rework because feasibility is discovered early. Fewer clarification loops because the prototype behaves like the real thing. Less drift because implementation is not a second interpretation.

This is not a tool preference. It is a business preference.

One warning, because enterprise reality always bites.

A code prototype can become a lie, too.

If a designer builds something that “works” in a sandbox but contradicts how the real codebase handles state, data, or security, you just created shadow engineering. It will feel fast right up until it hits production.

This is why the System Contract cannot be authored in isolation. It needs an engineering anchor. Co-author it with a lead engineer, or at least get it blessed by one, so the constraints and the prototype match the architecture you actually run.

The System Contract, written for AI

Most enterprises already have a North Star. It lives in a deck. It belongs there.

What I am describing is different. It is the System Contract. It is the operational protocol that keeps designers, engineers, and agents from wandering.

Think of it as two layers.

One layer is human-readable, for intent and judgment.

The other layer is machine-readable, for enforcement. That machine-readable layer is the Constraint Stack.

In an AI workflow, ambiguity is fuel. Your contract has to become computationally clear. Not poetic. Not inspirational. Clear.

The System Contract is not a statement. It is a package of constraints.

It includes:

- Non-goals: what you refuse to build.

- Invariants: rules that must stay true.

- State model: the states and the transitions, including failure states.

- Data contracts: inputs, outputs, required fields, error cases.

- Acceptance checks: what “done” means in behavior.

- Design system bindings: which tokens and components are allowed.

If that sounds like “engineering,” good. It is also design. It is design at the system level.

This is where a lot of designers get stuck. Not because they lack taste. Because they lack systems thinking.

Systems thinking means you can see the ecosystem around the screen. You can see dependencies. You can see the downstream costs. You can see where a local improvement breaks the whole.

Without that, AI will happily help you ship features that make the product worse.

The handoff: turning the System Contract into the Constraint Stack

This is the transition that matters.

A System Contract becomes real when it is compiled into constraints that tools can enforce.

Here is the uncomfortable truth. Someone has to own that translation.

Sometimes a designer writes the structured bits. Sometimes a design engineer does. Sometimes a platform engineer does. Sometimes an agent formats it.

The title does not matter.

Ownership matters.

Here is the rule that keeps you honest.

Humans own the logic. Agents can help with formatting. Verification closes the gap.

One warning that saves pain: an agent will prioritize valid syntax over correct logic. A perfectly formatted, lint-passing file can still be functionally wrong.

Now, the part people skip when they are being optimistic.

Review is hard.

A 300-line machine-generated constraint file is not “clarity.” It is a different kind of fog. If you hand that to a busy designer and call it governance, you are going to get the most dangerous review in the world. A fast one. Lots of “LGTM.”

So the Constraint Stack has to be reviewable, not just generatable.

If your review tooling is weaker than your generation tooling, you will rubber-stamp. That is not a character flaw. It is what happens when cognitive load exceeds attention.

That means keeping constraints small and diff-friendly. It means rendering them into human views that are easier to scan. State diagrams. Checklists tied to acceptance checks. Summaries that explain what changed and why.

If your team cannot review the constraints with the same confidence as they review code, you just moved intent leakage from the UI to a text file.

Otherwise, you have created a new kind of debt. Documentation debt with a fancy name.

The single source of truth problem, and the only way out

Leaders hear “spec is truth” and “prototype is truth,” and their alarm bells go off. Two truths mean drift.

They are right.

The path out is to define one canonical source of truth and treat everything else as compiled artifacts.

In this approach, the System Contract is the truth.

The Constraint Stack is the machine-readable representation of that contract.

That contract includes the design tokens and component bindings, not just the product logic. The code prototype is a compiled result.

Sync is not free. Sync is not perfect on day one.

Treat it as a maturity curve.

Stage 0 is manual. You require a constraint update when behavior changes.

Stage 1 is soft enforcement. Checks warn when something is missing.

Stage 2 is hard enforcement. Checks block merges when conformance fails.

Stage 3 is the high-risk frontier. Automated attribute sync for specific fields that are safe to reconcile. Narrative stays human.

The point is not perfection. The point is preventing divergence.

If behavior changes in code, the constraints must change too. Same pull request. Same diff. Same accountability.

That is how you avoid creating a second truth.

DesignOps AI is automation and verification, not more meetings

DesignOps can become a bottleneck fast if it looks like governance theater. More gates. More forms. More approvals.

In an AI-accelerated workflow, that collapses.

DesignOps AI has to move toward automation and verification. Not because automation is glamorous. Because it scales.

Now the blunt part.

Automation is not compliance.

Automated accessibility tools catch the stupid mistakes so humans can focus on the hard ones. They catch missing labels, obvious contrast issues, missing headings, and broken focus order in simple cases. They do not reliably catch complex interaction failures, confusing language, cognitive load problems, or the places where a product is technically compliant and still unusable.

Treat automation like a filter, not a judge. It keeps bad work from slipping through when everyone is moving fast.

Accessibility is a good example, but it is not the only one.

The broader question is simple.

What can you verify early, automatically, and consistently, so people can spend their attention on the parts that require judgment?

Token usage. Component contracts. State-transition checks. Data contract validation. Basic conformance between stated behavior and implemented behavior.

If you ship fast and fail a WCAG audit, you did not ship fast. You shipped debt.

You do not need a perfect system to start. You do need to stop pretending that speed without verification is progress.

Figma is not dead. It becomes a UI authoring plugin

Here is where I land, and it is not a peace treaty.

I use Figma less and less as the place where design “lives.” I use it as an authoring surface for aesthetics, and as a fast way to clarify intent when language fails.

In this model, the repo is the source of truth.

Figma is a UI authoring plugin for the system. The important output is not a frame. It is the tokens, component attributes, and variant rules that end up versioned alongside the rest of the Constraint Stack.

In a healthy setup, those tokens flow downstream as a dependency. They get exported or synchronized into the repo. The System Contract consumes them through the Constraint Stack. CI verifies them. Code uses them.

If the Figma file is deleted tomorrow, but the repo still contains the exported tokens and component rules, you are fine. You lose a convenience, not the source of truth.

If the token flow is manual, call it what it is. A sync risk.

You can live with it early, but you should not pretend it will stay reliable without time and ownership. The point is to avoid two worlds that drift.

The hard truth: this workflow demands technical literacy, and it creates an identity crisis

I am going to say the quiet part.

A designer who cannot read basic code cannot reliably direct an agent when it hits a logic error.

You do not need to become a full-stack engineer.

You do need to become debug-capable.

That means you can:

- understand component structure at a high level

- follow data flow in simple cases

- interpret error messages and logs

- isolate variables and reproduce issues

- review a diff without panic

One more enterprise truth.

In many companies, designers do not even have access to the environments that make “debug-capable” possible. No dev build. No staging. No logs. No error reporting. No feature flag dashboard.

That is not a skill gap. It is a permissions gap.

This is a prerequisite for the model to work.

If you want designers to verify behavior, they must have read-only access to the evidence.

Staging URLs. Storybook or a component explorer. Error reports. Log views. Feature flag dashboards.

No access means no verification. No verification means you are back to arguing about what was “meant.”

It does not have to be write access. It has to be visibility.

Now the cultural friction.

A lot of senior designers hear this and feel insulted. Like they are being asked to become a junior developer.

Leaders need to name that tension instead of pretending it will resolve itself.

Reading a diff is not a demotion. It is accountability.

It is the difference between “I handed it off” and “I can verify what shipped.” It is the difference between a screen that looks right and a system that behaves right.

If you want this to scale, reward that behavior explicitly. Put it in career ladders and in performance language.

Then measure it.

Track an upstream catch rate. How many logic flaws, constraint mismatches, or missing edge cases are caught in the System Contract and Constraint Stack review, versus discovered later in the final engineering PR.

What you measure gets staffed. What you do not measure becomes volunteer work.

Also, give people permission to be beginners in public without losing status.

Otherwise, the middle of the org will reject the workflow on identity alone, even if the tools are perfect.

The talent pipeline problem

If execution is cheap, the old junior path breaks.

A lot of junior designers learned by producing screens in Figma. That work is shrinking fast.

So leaders have to create a new apprenticeship, and it has to pay rent immediately.

Treat junior and mid-level designers as the verification engine.

Their job is to protect the System Contract from being hallucinated by speed. They review changes to the Constraint Stack, they validate state coverage, they pressure-test edge cases, and they spot mismatches before the final engineering PR becomes a courtroom.

They still learn systems by touching the system, but the value is not “learning.” The value is upstream catches.

If you do not build this pipeline, you end up with a senior-only workflow that cannot scale for a large organization.

Leaders care about scaling. They care about the middle of the org, not the top 10 percent.

This is why the “design engineer” question shows up.

Some orgs solve it with a formal Design Engineer or Design Technologist role.

Others solve it by leveling up senior ICs and pairing them tightly with front-end or platform engineers.

Either way, someone owns the System Contract as a capability, including the Constraint Stack implementation.

The title is optional. The ownership is not.

And here is the enterprise reality.

If you do not allocate time for stewardship, it does not happen.

If it is not a real line item in planning, it becomes “nice to have” work that gets pushed to the edges of the week. The System Contract becomes a dead document. The constraints drift. The team goes back to shipping vibes and cleaning up later.

Enterprise reality is a zero-sum game.

To make room for stewardship, you have to stop doing something.

And you have to protect it.

Middle management will veto this without meaning to. Design managers are often measured on sprint velocity and predictable delivery. A System Contract looks like a slowdown in the first few weeks.

If you want the shift to survive, take sprint velocity off the scoreboard for the first 60 days of the transition. Measure upstream catch rate and rework instead. Otherwise, the team will get pushed back to Figma-only work just to hit quarterly numbers.

For most orgs, the first cuts are predictable.

Stop demanding high-fidelity prototyping for every change.

Stop treating pixel-perfect QA in a static file as the default definition of quality. Pixel-perfection in a static file is a hallucination. Real products run on dynamic data, edge cases, and failure states.

Stop re-litigating taste in late-stage reviews when the code already exists.

Trade static polish for functional reality. You get fewer surprises and less rework, which is the only trade that scales.

My actual process, in plain language

I do not start in code.

I start outside the build tools.

I brainstorm with AI in a clean context. I write a System Contract. I research. I interview. I synthesize. Sometimes I use NotebookLM. Sometimes ChatGPT. Sometimes Gemini. Sometimes I switch models midstream.

The point is not the model.

The point is that the truth lives in a durable place. A documentation folder. A repo. A set of constraints.

When I move into prototyping, I want the agents to execute against something stable. I do not want wandering. I do not want creative guesses.

When I learn something new, I update the constraints, not just the prompt.

Strategy, research, ideation, build. Same process we have used for decades.

AI just made the execution layer faster.

The leak test: find the leaks you have been paying for

The fastest way to see what this is costing you is to look at your last three shipped features.

Not to assign blame. To see the bill.

A few questions usually expose the bill.

Where did intent leak between design and the merged pull request?

How many times did engineering ask, “What did you mean here?”

How many times did design say, “That is not what we designed,” after implementation?

Now the question that exposes maintenance leakage:

If you had to change that feature today, would the team know how?

Would they have the context?

Or would they be guessing based on a file and a dead chat log?

That gap is your opportunity.

A final thought

In mentoring sessions, I keep hearing the same pattern.

Teams are moving faster than they have ever moved, and they are more exhausted than they have ever been. Not because the work is harder, but because the corrections come late.

Late corrections do not just cost money. They cost morale.

People stop trusting the process. They stop trusting each other. The best people start looking for exits because they are tired of being efficient at the wrong thing.

“The more efficient you are at doing the wrong thing, the wronger you become.”

Russell Ackoff