AI insights

-

What is the main takeaway from the article 'RTFC (Read The Full Contract): If It’s Signed, It’s Real'?

The main takeaway is that in uncertain times, contracts can be a source of exploitation not through malice but through paperwork, emphasizing the importance of reading and understanding the full contract before signing.

Topic focus: Core Claim -

What does the article suggest about the nature of contracts in the current job market?

The article suggests that contracts can be a hidden source of exploitation for independent workers, as companies may not intentionally exploit contractors, but the terms written in contracts can lead to unintended consequences.

-

Why is it important to read the full contract according to the article?

It is important to read the full contract because if something is written down and signed, it becomes binding, and not understanding the terms can lead to being taken advantage of, especially in uncertain job markets.

Topic focus: Data Point -

What practical step does the article recommend for protecting your interests in a contract?

The article recommends confirming terms in writing to protect your interests, ensuring that all agreed-upon terms are clearly documented and understood by both parties.

Topic focus: Next Step -

What misconception about contracts does the article aim to clarify?

The article clarifies the misconception that companies intentionally exploit contractors, highlighting instead that exploitation often occurs through the terms of the contract itself, not through deliberate malice.

-

How does the article 'RTFC (Read The Full Contract): If It’s Signed, It’s Real' relate to the challenges faced in UX portfolios as discussed in 'The Carbon-Copy Crisis'?

Both articles highlight the importance of clarity and understanding in professional documentation, whether it's a contract or a UX portfolio, to avoid pitfalls and ensure that one's work and terms are clearly communicated and understood.

Topic focus: How To -

What further reading is recommended for understanding the importance of adapting to change in professional settings?

For understanding the importance of adapting to change, the article 'Change Isn’t the Enemy, Comfort Is' is recommended, as it explores how resistance to change can derail progress and offers frameworks for driving meaningful transformation.

Topic focus: Next Step

- These days a lot of talented people go independent as roles stall and budgets shift.

- The contract is where the gamble happens, not in malice but in language.

- Here’s a contractor’s reality check: read every line, don’t onboard before you sign, and treat the written document as truth.

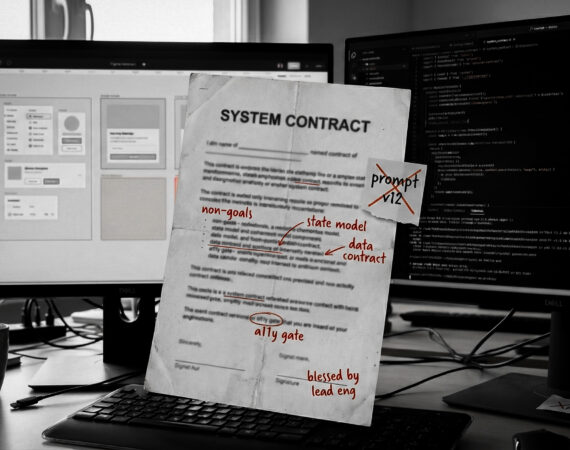

- Typical red flags: mismatches between what you discussed and what the SOW states about hours versus deliverables; IP language that claims your tools; non-solicitation; acceptance terms that stall payment; and sweeping liability without caps.

- The fix: pick a clear unit of work, carve out your IP, limit client restrictions, add an acceptance SLA, cap damages.

- If paper doesn’t match talk, walk away.

Right now, a lot of talented people are doing what they can to stay afloat. Full-time roles take longer to land. Budgets shift. Teams “pause hiring,” then quietly keep shipping anyway, just with contractors.

That means more designers (and developers, copywriters, researchers, PMs, pick your craft) end up going independent. Sometimes it’s a choice. Sometimes it’s the only open door that week.

And here’s the part nobody puts in the job post: in these uncertain times, the contract is where you can get used, not by malice, but by paperwork.

I’m not saying companies wake up plotting to exploit contractors. I’m saying something simpler and more dangerous:

If it’s written down and you sign it, it’s real.

(Quick note: not legal advice, this is a contractor’s reality check. Also, contracts might call you a “Consultant.” I’m going to call us contractors. Same human, same risk.)

The friendly call isn’t the deal

Recently, a company came to me with a genuinely interesting project, mixing product design and teaching, two things I enjoy the most. The conversations were normal: professional, upbeat, forward-looking. We talked about an hourly engagement. We talked about pace and bandwidth. We talked about doing the work in phases and possibly turning it into a longer-term relationship.

It felt like a reasonable independent contractor agreement in the making.

They even floated starting onboarding before anything was signed.

That’s a red flag. Don’t do it.

Then the Contract and Statement of Work (SOW) arrived.

When I pointed out the gaps, hourly on the call, deliverables on the page, the answer came back in the most common dialect of contracting: “That’s standard.” Sometimes it’s said gently. Sometimes it’s said like the conversation is over.

But “standard” isn’t the same as “safe.” It’s just the default setting.

And suddenly the shape of the deal changed. The paper leaned heavily toward pay‑per‑deliverable, even though the conversations had been anchored around hourly. The unit of work was fuzzy. The unit of pay was… different. A few terms weren’t defined, which is a polite way of saying the contract left room for someone else’s interpretation later.

So I did what I wish more of us did sooner: I read it. Slowly. Line by line. Like it mattered.

Because it does.

Why this matters

When you’re contracting, you don’t have the cushion a full-time employee has. No internal HR to mediate. No manager to escalate to. No paid time to “work it out.” You have a calendar, a bank account, and the words you signed.

That’s why contract review isn’t “being difficult.” It’s basic self-respect.

And it starts with one uncomfortable fact:

The negotiation you remember is not binding. The document is.

If it’s verbal, it can be rewritten

I’m all for real human conversation. I like getting on a call, finding common ground, and building trust. But relying on a verbal agreement is a gamble you shouldn’t take.

The problem isn’t necessarily malice; it’s that human memory is flawed. Verbal agreements get misheard. They get misinterpreted. Or, in the chaos of a project launch, they simply get forgotten.

And here’s the mechanism that quietly kills the friendly call: most contracts include an “entire agreement” clause, language that says this document supersedes all prior discussions. That clause doesn’t care how aligned you felt on the call. It wipes the whiteboard clean.

Three months from now, when you’re sure you agreed to “Net 15,” and they are certain they heard “Net 45,” the good vibe won’t save you. The written document is the only tiebreaker that matters.

So here’s a habit I’m begging you to build: after every call, send a follow‑up email.

“After our conversation, here’s what I understood. Please confirm.”

Keep it simple. Bullet points. The stuff that matters:

- Rate and unit (hourly vs per deliverable)

- What counts as a deliverable (and what doesn’t)

- Payment trigger (invoice timing) and acceptance timeline

- Ownership and licensing (what they get to use vs what you keep)

- Any non‑solicit boundaries

Because otherwise it becomes “we talked about it.” And in contract land, “we talked about it” is the same as “it didn’t happen.”

Red flag #1: The mismatch problem. What you discussed vs. how you get paid

Here’s the first red flag: when the contract tells a different story from the conversations.

In the SOW, I saw language that looked like “we expect weekly availability,” but then payment was framed as “you get paid when you deliver modules.” Both models can be fair on their own.

The problem is when they’re mixed in a way that gives the client the control of an hourly employee (blocking your time), but the risk profile of a vendor (paying only for approved output). That’s how contractors get squeezed: your calendar gets reserved, but your paycheck stays conditional.

These are the kinds of lines that should make you sit up straight:

"Estimated hours: 120. Availability: 20 Hrs/ week."

"Payout will be done based on the actual no. of Modules delivered."

"Total number of Modules to be delivered: 6…"

If you can’t explain the payment model in one clean sentence: “I get paid X for Y, within Z timeline,” it’s not ready to sign.

What I proposed: pick one clear unit of work (hours or modules), define it, and cap it. If it’s modules, define what a “module” includes. If it’s hours, cap it. If it’s both, make the relationship explicit (example: “up to 120 hours for 6 modules,” and what happens if feedback expands the work).

Red flag #2: The IP trap. When your methods quietly become theirs

This is the one that keeps senior contractors up at night: IP language that tries to own more than the deliverable.

In this contract, “Work Product” wasn’t just “the thing you’re delivering.” It explicitly reached into “derivatives” of what you already own.

"Work Product means… ‘…derivatives of pre-existing technology owned by Consultant…’"

And then it swung the door wide open:

"all Work Product is the sole and exclusive property of Company."

"The Work Product may not be used by Consultant for any purpose other than the benefit of Company."

In the exhibit, the examples got even more specific about what they might try to capture:

"Examples of Innovations… ‘methodologies… processes, tools, know-how…’"

"all innovations will be the sole and exclusive property of Client…"

Let’s translate that into human language: if you’ve built frameworks, templates, exercises, reusable systems, your career toolkit, this kind of wording can read like you’re handing it over.

What I proposed: a Background IP carve-out. I keep my pre-existing tools, templates, and know-how. If any of that is embedded in the deliverable, the client gets a limited license to use what they paid for.

Not to own my whole engine. Just to drive the car we built together.

Red flag #3: The non-solicitation landmine, “prospective clients”

Employee non-solicit can be normal. Nobody wants their team poached.

But when a contract starts restricting your ability to work, especially with language that includes “prospective clients,” you need definitions, boundaries, and limits.

Here’s the kind of thing I saw:

"for a period of one (1) year…"

"solicit the business of any customer or client of Company (other than on behalf of Company)."

And then the exhibit went further:

"consultant shall not solicit the business of any client or prospective client of Company, Client…"

"consultant shall not directly or indirectly compete with Company… with any client or prospective client…"

“Prospective client” can be a black hole. Undefined, it can mean anyone the company has ever talked to, anyone they hope to talk to, or anyone they might someday pitch.

That’s not a business relationship. That’s a leash.

What I proposed: keep the employee non-solicit. Narrow any client/account restriction to named client(s) under this SOW, only where I worked directly, limited to similar services, and ideally non-solicit only, not vague “compete” language.

Red flag #4: Acceptance can become an invoice hostage

A lot of SOWs tie payment to “delivery and acceptance.” Fine, until “acceptance” has no clock.

In this SOW:

"The Contractor may invoice after delivery, and acceptance, of every Module."

Without a definition and a timeline, “acceptance” can become a payment delay button. People get busy. Stakeholders change. Priorities shift. And suddenly you’ve finished the work, but you’re waiting for a green checkmark that isn’t required to show up.

What I proposed: an acceptance SLA (example: accept/reject within five business days or it’s auto‑accepted, sometimes written as “deemed accepted”) and a reasonable revision limit (example: two rounds unless the scope changes).

Red flag #5: Unlimited downside for a short contract

Even if everything else is negotiable, this one is about basic math: a short contract shouldn’t carry enterprise-scale liability.

The indemnity language I saw was broad and open-ended:

"indemnify, defend and hold harmless… against any and all claim, loss, damage… arising directly or indirectly from…"

“Any and all” + “directly or indirectly” is the kind of phrase that can swallow a lot.

What I proposed: a liability cap (fees paid, or 2× fees), exclusion of indirect/consequential damages, and indemnity limited to proven negligence/willful misconduct and IP issues from my original work (not downstream edits by others).

Yes, reading contracts is boring. Do it anyway.

I get it. You didn’t get into design (or development, or writing) because you love reading boilerplate.

But contracts are counting on your boredom. They’re counting on your optimism. They’re counting on you wanting the work badly enough to skip the slow part.

And they’re counting on one more thing: that you’ll hear “standard” and treat it like a stop sign instead of an invitation to clarify what you’re actually agreeing to.

So treat this like a safety check, not a personality test.

What I wish every contractor heard earlier

Read the contract before you sign. Then read it again when you’re tired. If it still feels off, it’s off.

If you need a simple north star, it’s this:

- Does the paper match what we discussed?

- Does it protect my ability to keep working after this project?

- Does it cap my downside so a small gig doesn’t carry big-company risk?

If a company won’t clarify mismatches, won’t define terms, or won’t engage with reasonable edits, that’s not a minor inconvenience.

That’s information.

You don’t need paranoia. You need clarity.

Because once it’s signed, it’s real.

“The faintest ink is better than the best memory.” (Proverb)

If this helped, pass it to one person who’s about to sign something “standard.”

Quick recap

- The conversation isn’t binding. The contract is.

- Protect your Background IP and narrow non-solicit language, especially “prospective clients.”

- Define acceptance and payment triggers so you don’t finish work and wait forever.

You must be logged in to post a comment.